| Téma: Matematika |

|

|

| katáng |

|

Így is húzható a 67 db: 31 kék + 34 fekete + 2 piros

|

|

| Rendes Kis |

|

34 fekete,

21 fehér,

14 piros,

31 kék.

66 golyót tudok úgy húzni, hogy ne legyen közöttük fekete.

Ha 67-et húzok, abban már biztosan lesz mind a 4 féle szín. |

|

|

|

|

| tótumfaktum |

|

|

Az nem elég ha pl. csak 2 piros és 2 fehér golyó van a zsákban. |

|

|

| tótumfaktum |

|

Hát, nemtom, lehet hogy valamit nem vettem figyelembe, de nekem az jön ki,

hogy a fekete=47, piros=1, kék=51, fehér=1 felállás is teljesíti a feltételeket,

emiatt viszont mind a 100 golyóbist ki kell húzni ahhoz, hogy biztosan legyen benne minden színből legalább 1 pici darabocska, nem?...

|

|

| tótumfaktum |

|

Nem jó.

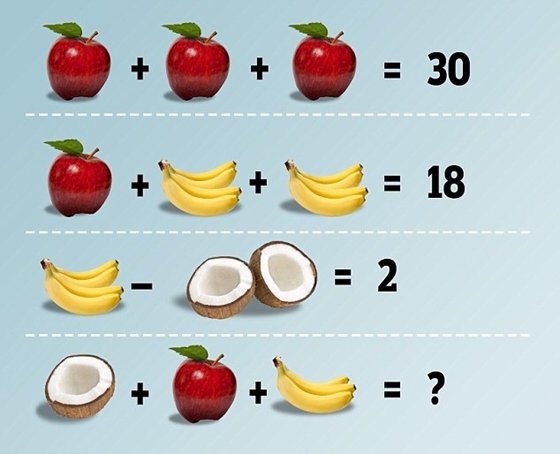

Az "alma"=10, "banán"=1, "kókusz"=2

Csak így jön ki helyesen az 1+10+3=14

|

|

| katáng |

|

Egy zsákban fekete, fehér, piros, kék golyókat helyeztünk, összesen 100 darabot. A zsákban lévő golyókról a következőket tudjuk:

a) 45 golyó nem fekete és nem is fehér;

b) 52 golyó nem fekete és nem is piros;

c) 35 golyó nem fekete és nem is kék.

Hány golyót kell becsukott szemmel kihúzni a zsákból ahhoz, hogy biztosan legyen mind a négy színű golyóból a kihúzottak között?

|

|

|

| negyven rabló |

|

Na, na!

Nincs félkókusz!

Idézet:

Á, itt biztos van valami ravaszság!

sztem:

első sor: 3x1 alma = 30, vagyis 10/db

második sor: 1 alma/10 + 8 banán/1, vagyis 1 banán = 1

harmadik sor: 4 banán minusz 2 kókusz= 2, tehát egy kókusz =1

utolsó sor: 1+10+3=14

Jó?

|

|

| Omniscient |

|

Nem, nem, mert akkor meg nem írhatnád ezt a levezetésben:

"harmadik sor: 4 banán minusz 2 kókusz= 2, tehát egy kókusz =1"

hanem, akkor így lenne esetleg helyes a szöveg:

harmadik sor: 4 banán minusz 2 félkókusz= 2, tehát egy félkókusz =1

Azért nem feltűnő, mert a negyedik sorba már nem írtál szöveget ...

|

|

| negyven rabló |

|

Sztem nincs fél kókusz. Darab van, mint ahogy darab a banán is!

Na mindegy! Tévedhettem is, de tetszett.  |

|

| menta |

|

|

hű, tényleg! ez jó! |

|

| Omniscient |

|

Valójában nem azonos értékűek azok sem. (Ez a másik "csel"  ) )

A Rabló úr végeredménye tökéletes, csak a levezetésnél van egy pici pontatlanság...

alma = 10

banán = 1

kókusz =2

Mer'hogy a fél kókusz = 1, az utolsó sorban ..

|

|

| menta |

|

|

csak egy banánhéjon: ) |

|

| mackó |

|

Na, igazad van, a csomag banánon elcsúsztam ...

Rabló uram, felületes szemlélő voltam! |

|

| menta |

|

hm, én is pont így dőltem be, mint 45. De a 40/44 a jó. És el is gondolkodtam, miért dőltem be. Mert a banán elfordítottan szerepel és azt nem néztem meg figyelmesen (áá, azt tudom) Látványban állandóan kiegészítjük a tudomásunkkal azt, amit látunk.

Ez az egyik csel, másik kicsit furcsa, hogy a kókusz is, és a banán is 1 értékű. |

|

| mackó |

|

Szerintem:

1 sor: Alma=10 (3x10=30)

2.sor: 10+2xBanán=18, azaz Banán=8/2=4

3. sor: 4-2xKókusz=2, azaz Kókusz=2/2=1

4. sor: 1+10+4=15 |

|

| negyven rabló |

|

Á, itt biztos van valami ravaszság!

sztem:

első sor: 3x1 alma = 30, vagyis 10/db

második sor: 1 alma/10 + 8 banán/1, vagyis 1 banán = 1

harmadik sor: 4 banán minusz 2 kókusz= 2, tehát egy kókusz =1

utolsó sor: 1+10+3=14

Jó? |

|

|

| Rendes Kis |

|

Science and Islam, Jim Al-Khalili - BBC Documentary

Közzététel: 2013. márc. 27.

Science and Islam, Jim Al-Khalili.

BBC Documentary

Science and Islam is a three-part BBC documentary about the history of science in medieval Islamic civilization presented by Jim Al-Khalili. The series is accompanied by the book Science and Islam: A History written by Ehsan Masood.

Episodes:

Part 1: The Language of Science

Part 2: The Empire of Reason

Part 3: The Power of Doubt

Part 1: The Language of Science:

Physicist Jim Al-Khalili travels through Syria, Iran, Tunisia and Spain to tell the story of the great leap in scientific knowledge that took place in the Islamic world between the 8th and 14th centuries.

Its legacy is tangible, with terms like algebra, algorithm and alkali all being Arabic in origin and at the very heart of modern science - there would be no modern mathematics or physics without algebra, no computers without algorithms and no chemistry without alkalis.

For Baghdad-born Al-Khalili this is also a personal journey and on his travels he uncovers a diverse and outward-looking culture, fascinated by learning and obsessed with science. From the great mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, who did much to establish the mathematical tradition we now know as algebra, to Ibn Sina, a pioneer of early medicine whose Canon of Medicine was still in use as recently as the 19th century, he pieces together a remarkable story of the often-overlooked achievements of the early medieval Islamic scientists.

Part 2: The Empire of Reason:

Physicist Jim Al-Khalili travels through Syria, Iran, Tunisia and Spain to tell the story of the great leap in scientific knowledge that took place in the Islamic world between the 8th and 14th centuries.

Al-Khalili travels to northern Syria to discover how, a thousand years ago, the great astronomer and mathematician Al-Biruni estimated the size of the earth to within a few hundred miles of the correct figure.

He discovers how medieval Islamic scholars helped turn the magical and occult practice of alchemy into modern chemistry.

In Cairo, he tells the story of the extraordinary physicist Ibn al-Haytham, who helped establish the modern science of optics and proved one of the most fundamental principles in physics - that light travels in straight lines.

Prof Al-Khalili argues that these scholars are among the first people to insist that all scientific theories are backed up by careful experimental observation, bringing a rigour to science that didn't really exist before.

Part 3: The Power of Doubt:

Physicist Jim Al-Khalili tells the story of the great leap in scientific knowledge that took place in the Islamic world between the 8th and 14th centuries.

Al-Khalili turns detective, hunting for clues that show how the scientific revolution that took place in the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe had its roots in the earlier world of medieval Islam. He travels across Iran, Syria and Egypt to discover the huge astronomical advances made by Islamic scholars through their obsession with accurate measurement and coherent and rigorous mathematics.

He then visits Italy to see how those Islamic ideas permeated into the West and ultimately helped shape the works of the great European astronomer Copernicus, and investigates why science in the Islamic world appeared to go into decline after the 16th and 17th centuries, only for it to re-emerge in the present day.

Al-Khalili ends his journey in the Royan Institute in the Iranian capital Tehran, looking at how science is now regarded in the Islamic world.

... www.facebook.com/peter.renner.54?fref=ufi |

|

|

|